Illusions the Art of Magic Posters From the Golden Age of Magic

Arts & Civilisation |

The Astonishing Poster Art From the 'Golden Age' of Magic

An exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario shows how magicians enticed audiences with advertisements of levitations, decapitations and other deceptions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/ae/60aebf70-d3b3-4729-bc9d-dffc724a6475/illusions_kellar_and_his_perplexing_cabinet_mysteries_social.jpg)

At the plough of the 20th century, magician Harry Kellar commissioned a poster to annunciate 1 of his near famous tricks, "The Levitation of Princess Karnac," in which he appeared to make a hypnotized adult female—whom he claimed was a Hindu princess—hover in mid-air. The illustrated poster depicts Kellar dressed in a strong tuxedo with his hands held above a floating, raven-haired woman. Two rows of little crimson devils bow at the sorcerer'due south feet, as though supplicating a supreme figure of dark and mysterious powers.

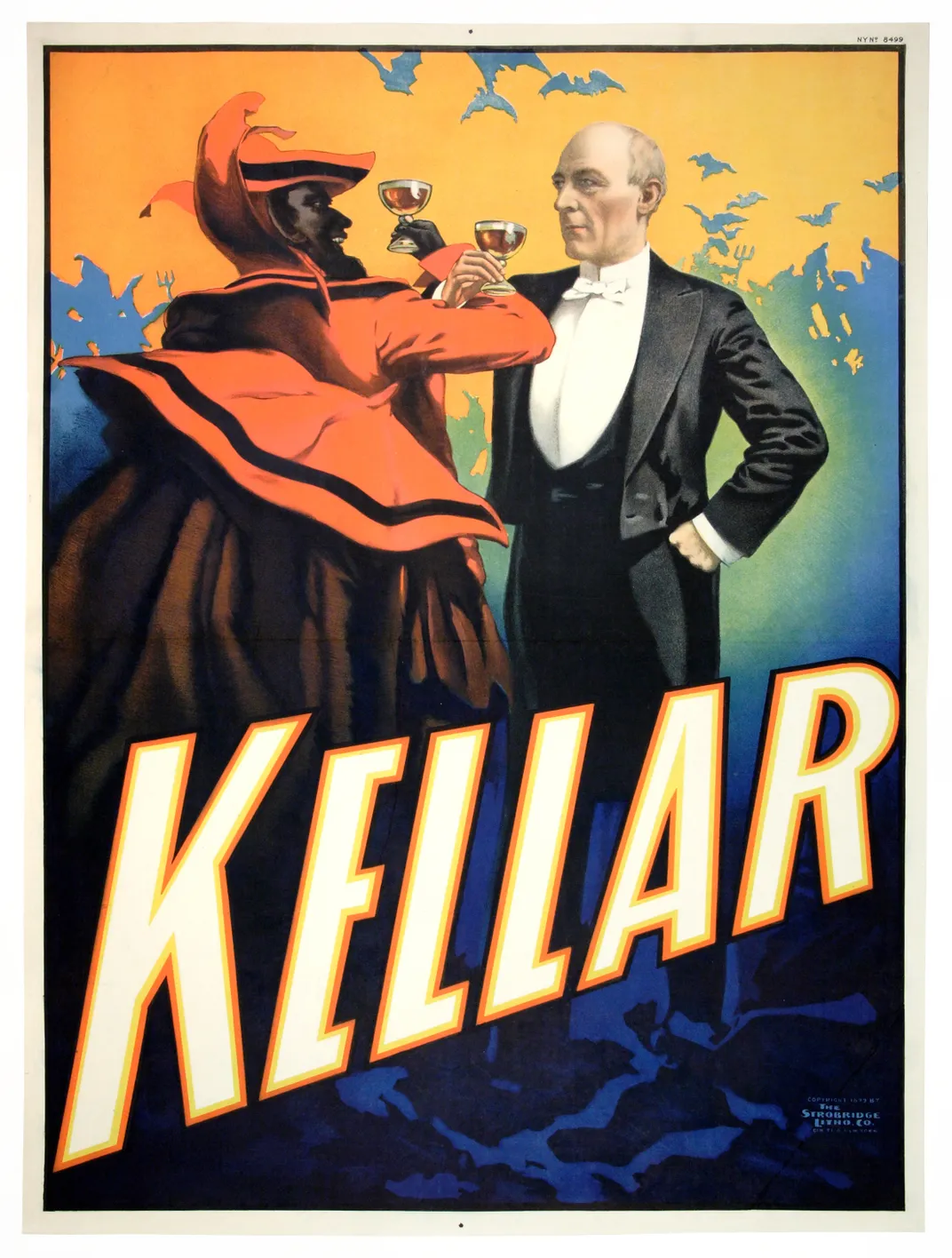

Though his proper noun has been all but forgotten, Kellar was once a pioneering showman and global star. He staged large, lavish shows, during which fans might run into him make live canaries disappear, or even decapitate himself. Posters were key to enticing audiences to his productions; they often show the magician conversing with devilish figures, every bit if in league with them—a promotional ploy that proved irresistible to Victorian audiences.

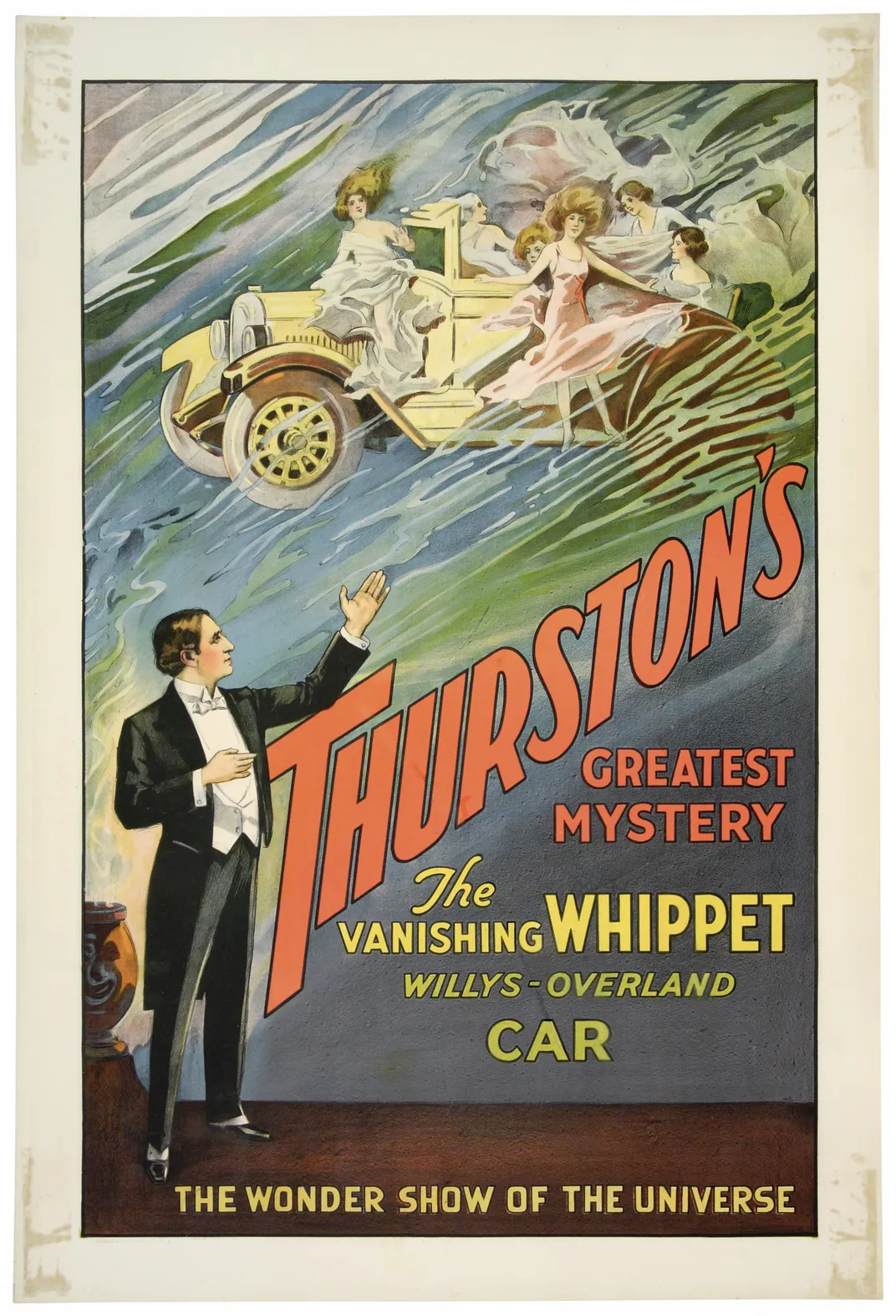

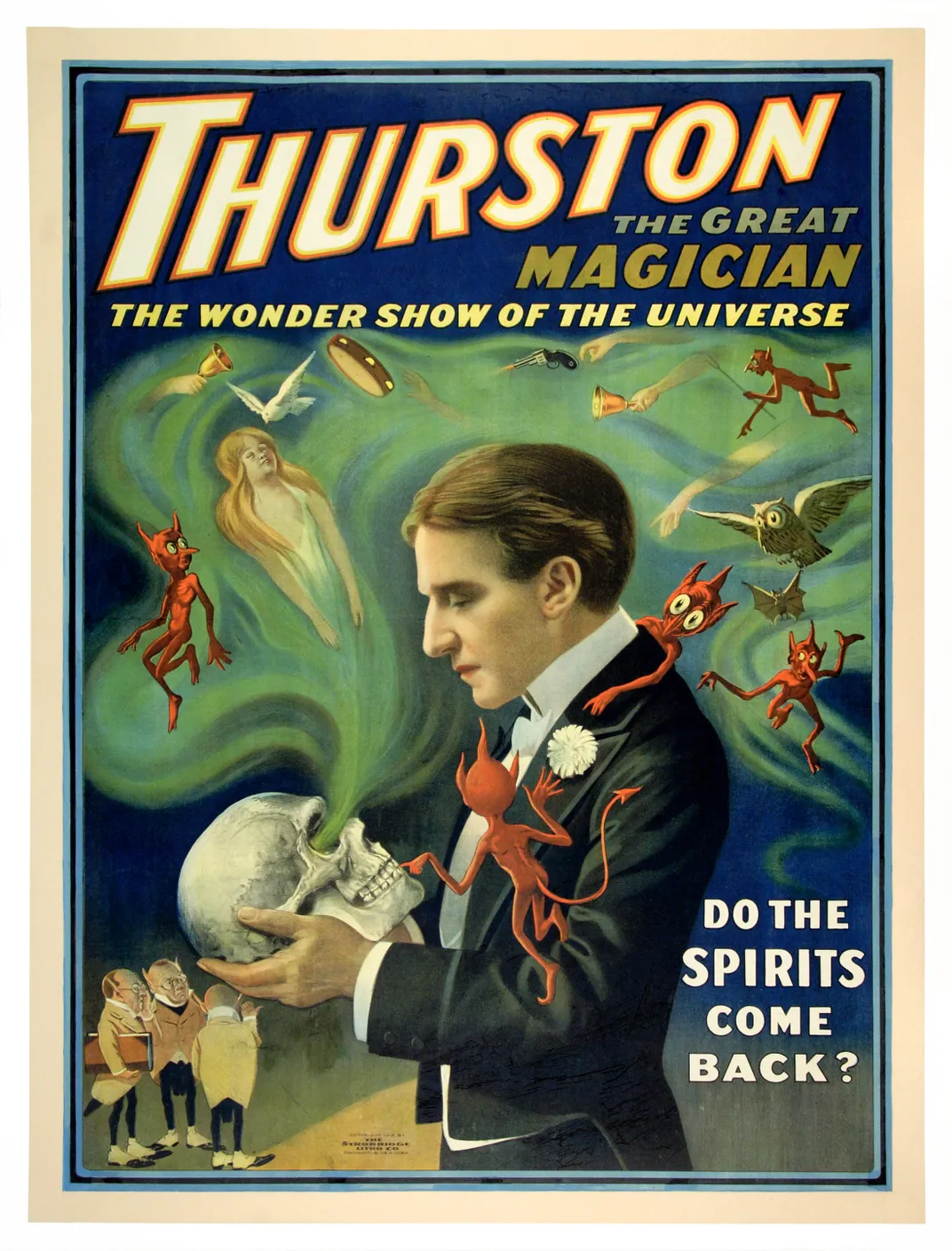

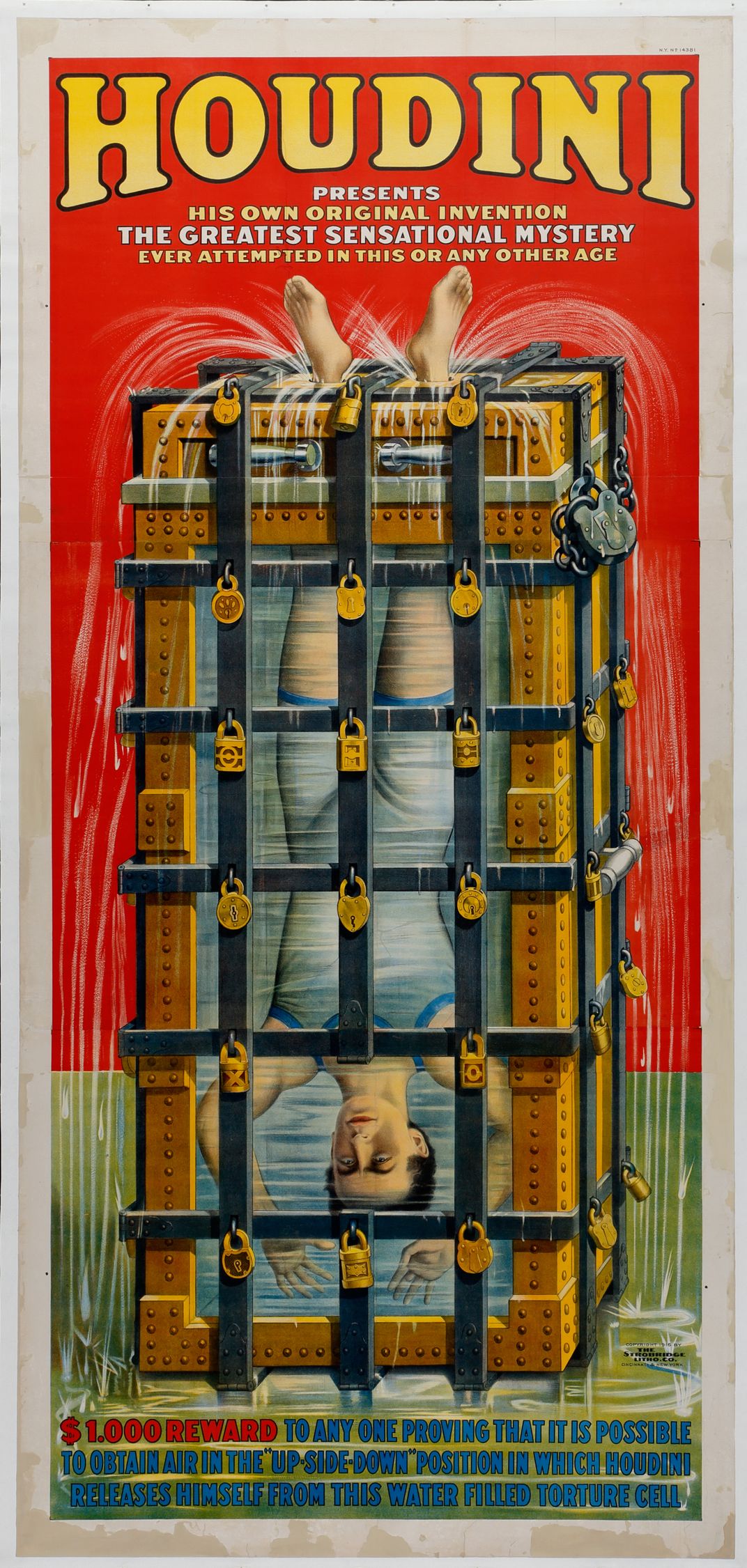

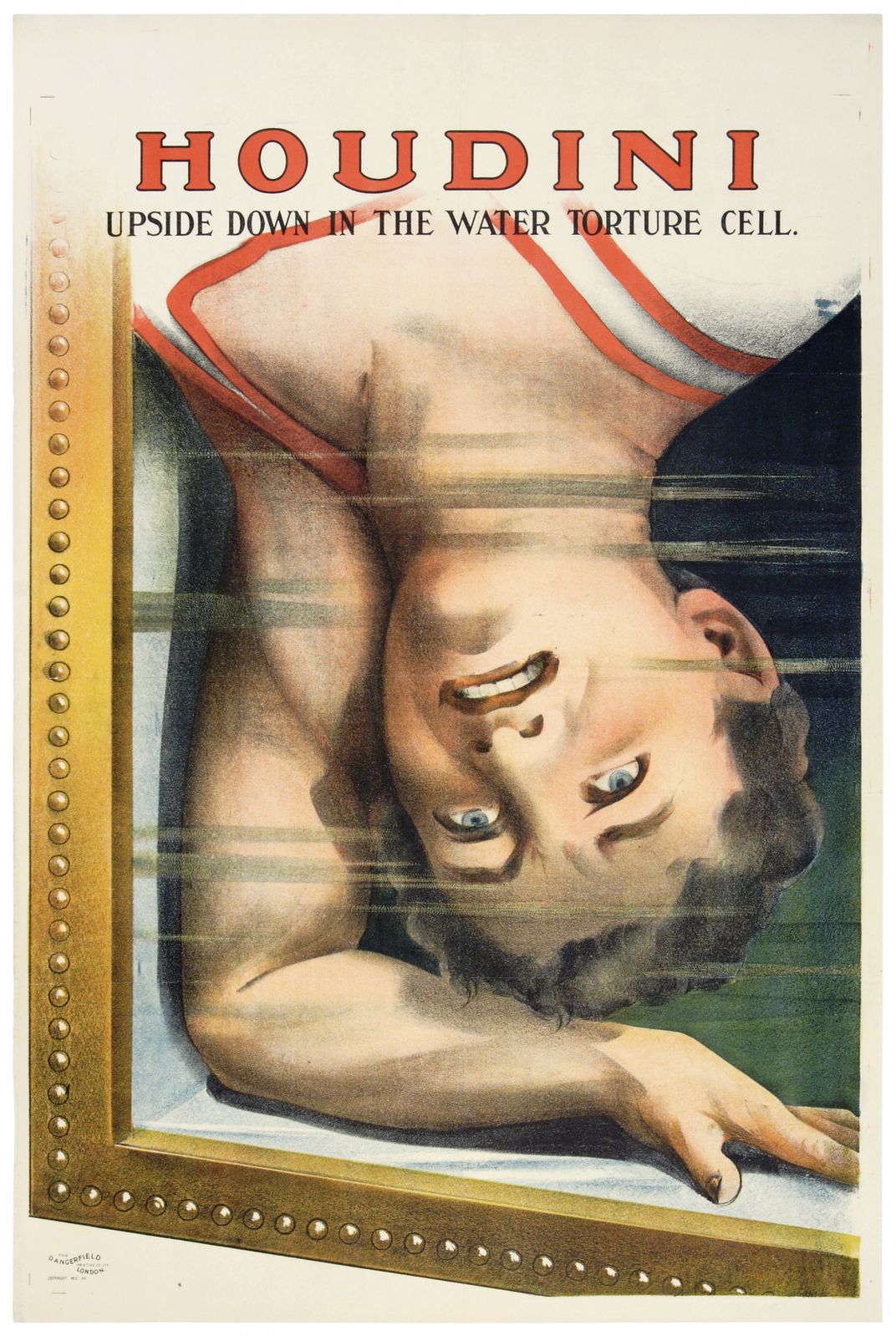

A selection of Kellar'southward ads are among 58 historic magic posters on brandish at "Illusions: The Art of Magic," a new exhibition at Toronto's Art Gallery of Ontario. The show explores the fantastic feats and sensational showmanship of performers during magic'southward "Gold Age"—a period that spanned roughly from the 1880s to the 1930s and saw magicians soar to unprecedented heights of international celebrity. Colorful and alluring, the posters are rife with headless figures, floating cards, crystal balls and big promises. "The greatest sensational mystery ever attempted in this or whatever other age!" declares an ad for Houdini's Chinese water torture cell act. "The wonder show of the universe!" cries a poster flaunting a performance past Howard Thurston, who could seemingly brand a automobile vanish into thin air.

"Imagine [seeing] these on billboards when you're walking in your town," says David Ben, guest curator of the exhibition and a magician who performs on both stage and screen. Ben start became enthralled with magic when he was 12 years old, after his begetter gave him a magic handbook. He began studying the lives and careers of the performers who came earlier him, and today publishes a magic history journal. Looking around at the posters that line the Ago exhibition space, Ben admires his predecessors' boldness.

"These guys were broad," he says, puffing out his chest. "They played the room."

A number of factors fueled the ascension of superstar magicians in the late 19th century, including the burgeoning popularity of vaudeville in the belatedly 1800s. Consisting of 10 to 15 short acts, these variety shows offered opportunities for "even a guy with a menu human action to become a star if he was good enough," explains Houdini skilful John Cox, author of the blog Wild About Harry .

"Houdini was a star of vaudeville," Cox notes. "It wasn't until the end of his career that he even did a full evening magic evidence like we assume that he did…. Magicians played vaudeville, but a lot of them found it was more than profitable to actually go out and tour on their ain."

With the growth of railway networks in America, along with the appearance of steamships every bit a mode of international travel, intrepid performers took their acts beyond the state and across. For instance, Charles Joseph Carter, an American magician known past the stage proper noun "Carter the Smashing," embarked on eight world tours between 1900 and 1936, traveling largely in the Eastern Hemisphere—and taking 22 tons of equipment along with him. Carter'south fourth dimension abroad inspired his persona; in one affiche on view at the AGO, he is depicted in white safari gear, sitting astride a camel. The bottom of the ad promises that the magician "sweeps the secrets of the sphinx and marvels of the tomb of the onetime King Tut to the modernistic world." Carter happened to share a last name with Howard Carter, who discovered the pharaoh's tomb in 1922—and according to Ben, the sorcerer was more than happy to capitalize on any associations with the famed archaeologist.

"I love it," Ben says of the poster. "That sense of puffery is show biz."

The rising of chromolithography—a color printing technique that involved transferring sketches onto rock printing slabs and adding colors in layers, each colour typically needing its own rock—bolstered magicians' self-promotional flair. Chromolithography became increasingly popular in the wake of the American Civil War, in large part because information technology was cheap; by the 1880s, the procedure was widely used in advertisement. A range of theater performers relied on chromolithograph posters to flaunt their talents, but magicians "really, actually took advantage" of the technology, according to Cox. "They could admittedly grip you with their posters. They would plaster cities with these things."

The posters may have been relatively inexpensive, but it took a team of skilled craftspeople to brand them: fine art directors who would come up with the concept for the design, artists who specialized in tracing lettering and other motifs onto lithographic stones, yet other artists who filled in the outlines with vibrant colors. Some companies were more than highly regarded than others; in America, the Strobridge Lithographing Company was considered to be one of the best, creating ads for the likes of Kellar, Thurston and Houdini.

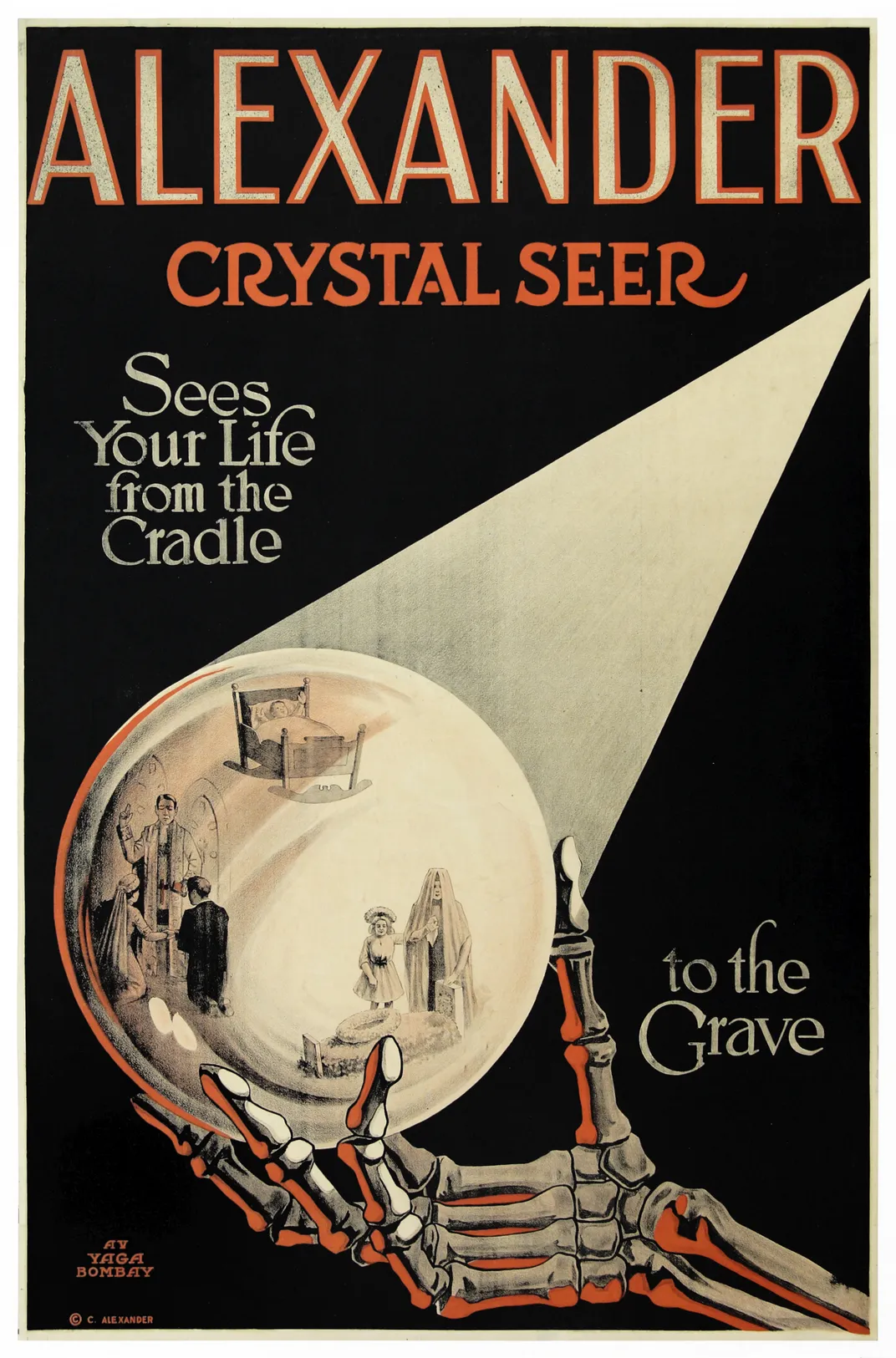

"Illusions: The Art of Magic" highlights a range of artistic styles and sensibilities. A poster by the Dangerfield Printing Visitor features a shut-up portrait of a grimacing Houdini, trapped upside down in his water torture cell. A skeletal hand clutching a crystal brawl stretches across an advert promoting the "seer" Alexander—an American performer (real name: Claude Alexander Conlin) who wowed audiences with his power to read minds. Even so some other poster, this one by Strobridge, depicts Kellar against a deep blue and vibrant orange properties, linking arms with a dastardly figure, probably Mephistopheles, as the duo beverage crimson wine. (At least occasionally, Kellar'due south inspiration sprang from not-satanic sources; his famed "Levitation of Princess Karnac" act, for example, was pilfered from the English magician John Nevil Maskelyne.)

The various assortment of posters featured in "Illusions" is on loan from the McCord Museum in Montreal, which is home to the Allan Slaight Drove of more 600 chromolithographs and 1,000 items related to Houdini. Arguably still the world'south most famous sorcerer, Houdini is nowadays throughout the exhibition; in add-on to several of his chromolithograph ads, one of his straightjackets is on display. But Ben says curators did not want to "get super huge" on the chief escape artist. Instead, they sought to showcase a selection of posters that "introduce united states to who the prominent players were that, with few exceptions, time has forgotten."

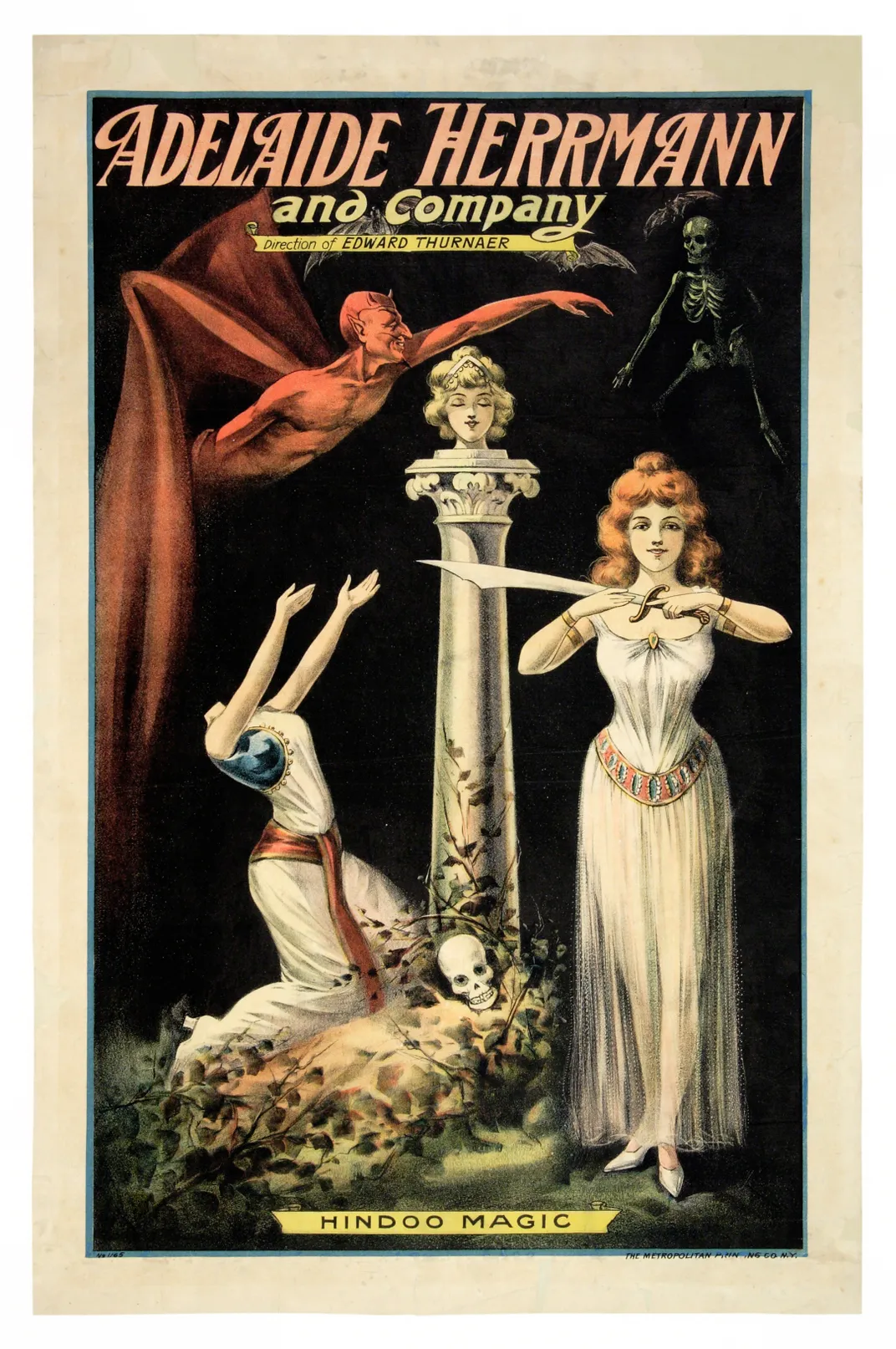

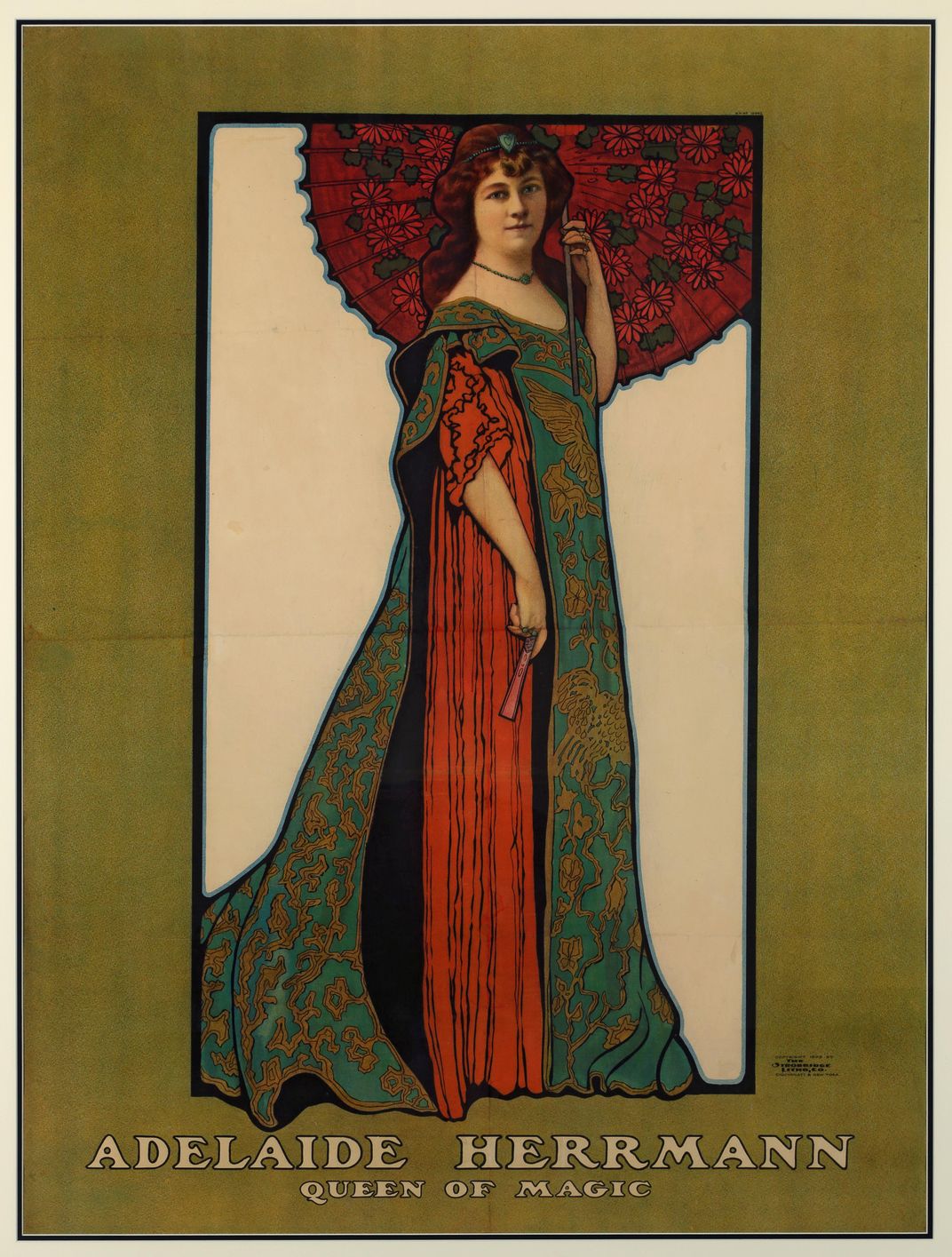

I department of "Illusions" spotlights the little-known female magicians of the Gold Age. Women make frequent appearances in the exhibition's posters as the passive objects of male showrunners' tricks: they are levitated, decapitated, sawed in half, shot through with arrows. Just some became successful headliners in their own correct. Adelaide Herrmann, for instance, was married to the French performer Alexander Herrmann, one of the most popular magicians of the late 19th century. She began her magic career equally Alexander's assistant, but when he died in 1896, she took over his human activity. Adelaide wore pants and a white blouse on stage, levitated and decapitated female person assistants, and defenseless bullets with her bare hands. Audiences in N America and Europe loved her, and she toured major vaudeville circuits until she was in her seventies. A poster on view at the AGO hints at her supremacy within the field. She is depicted alone, wearing a sumptuous dress of red, blueish and gold. "Adelaide Herrmann," the text reads, "Queen of Magic."

The exhibition also calls attention to the appropriation and caricaturing of Eastern cultures past Golden Historic period magicians, an unsettling practice that is evident in many of the posters on display. Fueled in part by the advent of railroads and steamships, which opened upward new lands to Western travelers, Americans and Europeans of the 19th century developed a fervent fascination with the Heart Eastward, Due north Africa and Asia—a fascination that in turn inspired exoticized representations of the East in art, literature and even interior decorating trends. Magicians, always the opportunists, freely took advantage of the craze.

In one corner of the gallery hangs a poster depicting a man in a red robe and peacock feather cap, with a long braid dangling over his shoulder. White lettering announces the performer as "Chung Ling Soo"—whose real name was William Ellsworth Campbell Robinson. Built-in in New York in 1861, Robinson modeled his persona after Ching Ling Foo, a conjurer who did in fact hail from China. Robinson pantomimed his style through his acts, never speaking on stage—until 1918, when one of his bullet tricks went terribly incorrect and he received a mortal wound. "Oh my God," Robinson reportedly cried out in perfect English language. "Something's happened. Lower the drapery."

Orientalism was not the only idea that magicians incorporated into their phase acts. When spiritualism, a religious movement rooted in the thought that the souls of the expressionless can communicate with the living, took off in the mid-19th century, some magicians began bringing supernatural elements to the stage. Thurston, who reportedly believed in spiritual phenomena, performed "Spirit Chiffonier" illusions. The wizard might place a tambourine, cane and bell into an empty cabinet and close the door. Of a sudden, the props would showtime rattling—a sign that the spirits were present. The effects would build from there, with objects like a large sphere or a handkerchief floating out of the chiffonier. In one of his ads, Thurston can exist seen gazing downwards at a skull, ephemeral figures and disembodied arms swirling around his head. The bottom of the affiche asks a question that was likely on the minds of many of his fans: "Do the spirits come up dorsum?"

When it comes to how magicians of the Golden Age carried out their spirit-conjuring, bullet-communicable, straight-jacket-busting feats, "Illusions" does not reveal whatever secrets, preserving the sense of intrigue that performers sought to create from the moment they plastered their ads around town.

"These posters really ignited the imagination, because they played on mystery," Ben says. The goal, he adds, was not simply to fob audiences; Gold Age magicians created immersive experiences that opened people upward to new worlds, realms and possibilities.

"You don't see performers in this advertizement maxim, 'Nosotros'll fool y'all,'" Ben notes. "They want to take yous on a journey."

wilkinsonfookistand.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/art-golden-age-magic-posters-180974304/

0 Response to "Illusions the Art of Magic Posters From the Golden Age of Magic"

ارسال یک نظر